Michelle Allen is an occupational therapist for Chesterfield County Public Schools and serves students privately through Treehouse Pediatric Therapy. In the school system, occupational therapists help students access their social and academic environments, which completely changed during the pandemic.

“In an in-person classroom, we might be looking at positioning for seating or how students use pencils as well as observing sensory qualities of the environment in an effort to minimize distractions to students,” says Allen. “We help students who might need more support processing the foreground from the background and help them to understand what’s expected of them so that they have the opportunity to be as independent in their role as a student as possible, despite their disability or limitations.”

When the school system transitioned to virtual, remote learning, Allen was forced to make the switch from observing her students’ physical environments to scheduling screentime interactions.

Transitioning to teletherapy

Making the changeover to virtual sessions began with getting the equipment and technology needed to do virtual meetings while ensuring platforms were HIPAA-compliant – a process made easier thanks to the relaxing of telehealth rules and regulations in Virginia during the pandemic. Next came the modality of sessions with students.

“During in-person sessions, there is some down time when students are doing activities that allow me to collect materials to transition to the next activity. But on a Google-meet, I was in constant performance mode and had to keep my students engaged,” said Allen.

When providing virtual occupational therapy services, there were a variety of ways Allen delivered. She observed students in the virtual classroom, met one-on-one and in group sessions as well as interacted with parents or other caregivers using the Coaching Model.

“Sometimes my coaching didn’t involve interactions with the student at all, and I would meet with parents to discuss challenges and strategies that they could use to help their children,” said Allen. “Or I would need to work with caregivers to ensure all the material prep for activities were done ahead of my sessions with students.”

Benefits of online learning for students with special needs

There were many students on the spectrum who have reactive, behavioral challenges in the classroom that responded well to the highly visual information coming to them on the screen. These students also felt very comfortable at home, in their safe space, without the risk of other students bumping into them or unexpected sounds that might cause a student to physically react. Furthermore, students were in control of the volume of their classroom and had the ability to mute themselves and adjust volumes.

Built-in assistive technology features like closed captioning came in handy for students who had trouble keeping up with the audio speech.

“All of these benefits are what helped several of my students stay more engaged during lessons than they typically would in the classroom,” said Allen. “And the best part was that they looked like any other kid in a box on a screen – many of my students have behaviors or make sounds that might irritate other students or even the teacher.”

Strategies for students

Strategies for students

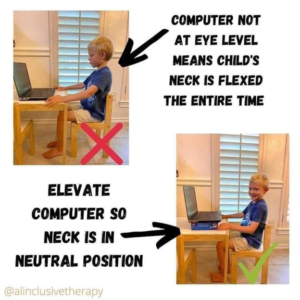

Figure Allen worked with students on fine motor coordination and core strength so that they could tolerate sitting at a desk for a longer period of time. And one of the most important elements in helping students practice these skills while adjusting to remote learning was creating an effective physical space that allows for good, comfortable posture. Figure 1 demonstrates a simple tactic for keeping a young students’ neck in a neutral position while working on a laptop.

Another important factor was taking breaks from long periods of seated time.

“Students were sitting in front of their computers all day, so we did activities to move their bodies, get their blood flowing and keep them engaged,” said Allen.

One of the activities Allen frequently used included interactive slide work with Google Slides. Each slide would have a minor transition, which allowed students to correlate a physical movement with a visual element. For example, during the winter Allen used snowballs, and each slide would take away a snowball while her student would physically pretend to dig in the snow.

“We would stand up together and I would have them dig. Every time we would ‘dig’, I would press the clicker and it would progress in the slide,” said Allen. “And they did have this idea that their bodies were making the slide change.”

While occupational therapists like Allen quickly adapted to meet the needs of students, documenting successes along the way as healthcare providers – both physical, mental and behavioral – continue to strengthen telehealth services for the long run, there is still work to be done to ensure patients of all ages, demographics, socio-economic status and those with other limitations have access to care.

“It was rewarding to see students who benefited from virtual learning, but these tactics didn’t work for everyone,” said Allen. “Some students with multiple siblings or multi-generational households had trouble finding a quiet space and similarly, many students with working parents had to be in a daycare, a sensory nightmare as it would be very noisy when they would speak into the microphone. When we look at what lies ahead, I think we need to be prepared for anything.”